An Unexpected Year at the Getty in Los Angeles

It has been a crazy past couple of months moving and settling in Chicago, but I have finally found my cadence in my new home to pen my thoughts about my incredible time in Los Angeles.

Like New York, LA was never part of my plans. It just never appealed to me. So when I learned I’d be spending 12-months there working at one of the finest museums in the world, no less I was equal parts surprised and thrilled. Life and luck continue to surprise me.

My time as the Collection Platforms & Data Graduate Intern at Getty Digital was nothing short of incredible. From day one, I was surrounded by an exceptional cohort of interns whose talent, tenacity, and generosity continuously put me in awe. Each brought unique expertise to the table: conservation science, decorative arts and sculpture, historic preservation. Every conversation became an opportunity to learn something new, and I found myself constantly inspired by the depth of knowledge this group shared so generously.

Working at Getty Digital felt like witnessing the future of museum technology unfold in real time. The team operates at a remarkable level, supported by Getty’s substantial resources, and I had a front-row seat to their innovative work. One of my highlights was diving deep into Getty Digital’s data ecosystem and pipelines: the infrastructure that powers their ambitious IIIF and Linked Open Data initiatives. Seeing how these systems work together to make collections more accessible was genuinely eye-opening.

The internship allowed me to develop skills across three key areas of digital preservation, each presenting its own unique challenges.

Web Archiving

I worked on preserving Getty’s legacy websites using tools like Archive-It and Browsertrix. What made this fascinating—and sometimes frustrating was that each site responded differently to different tools. Some sites captured beautifully with one approach but fell apart with another. The work required constant experimentation and problem-solving to achieve the best possible preservation outcome. There’s something satisfying about finding just the right combination of tools and settings to capture a site faithfully.

Time-Based Media Preservation

I also became acquainted with Rosetta, an Ex Libris product, where I ingested Getty Museum’s time-based media collection. The process involved file extraction, metadata injection, and validation. Meticulous work that required attention to detail at every step. One aspect I particularly enjoyed was working with file format signatures, where I had the opportunity to implement one developed by the intern before me. It felt like being part of a continuum of preservation efforts.

System Integration

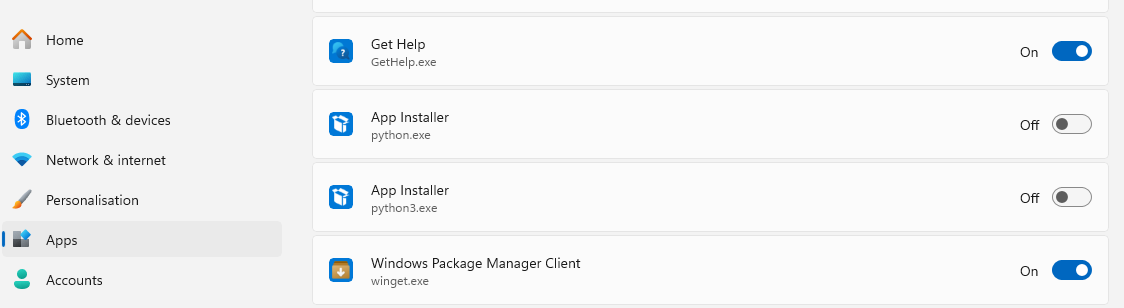

Perhaps the most eye-opening project was implementing Single Sign-On for Rosetta. I’d always wondered how SSO actually worked behind the scenes, and getting hands-on experience demystified the process entirely. Understanding how these authentication systems integrate with existing infrastructure gave me a new appreciation for the complexity of museum technology ecosystems.

This internship has been a springboard for my career in ways I’m still discovering. Beyond the technical skills, I’ve gained confidence in tackling complex digital preservation challenges and a clearer vision of the kind of work I want to pursue. I’m incredibly grateful to my manager, Teresa Soleau, for this opportunity and for her leadership, wisdom, and experience. She created an environment where I could grow, experiment, and learn from both successes and setbacks.

As I settle into Chicago and this next chapter, I carry with me not just new skills but a renewed sense of purpose about the importance of preserving our digital cultural heritage.